“The camera introduces us to unconscious optics as does psychoanalysis to unconscious impulses.”

— Walter Benjamin

Light has always both revealed and concealed. Its very nature invites fascination—and confusion. From ancient Greece to quantum physics, the story of optics is not merely about vision. It’s about how we’ve tried to see the world—and often failed, gloriously.

Ancient Glimpses: Greece to Islam

In the dusty shadows of ancient Greece, Euclid imagined light moving in straight lines. Ptolemy, more methodical, bent it through water and mirrors, experimenting with reflection and refraction. These were early stabs at understanding light—equal parts guesswork and geometry.

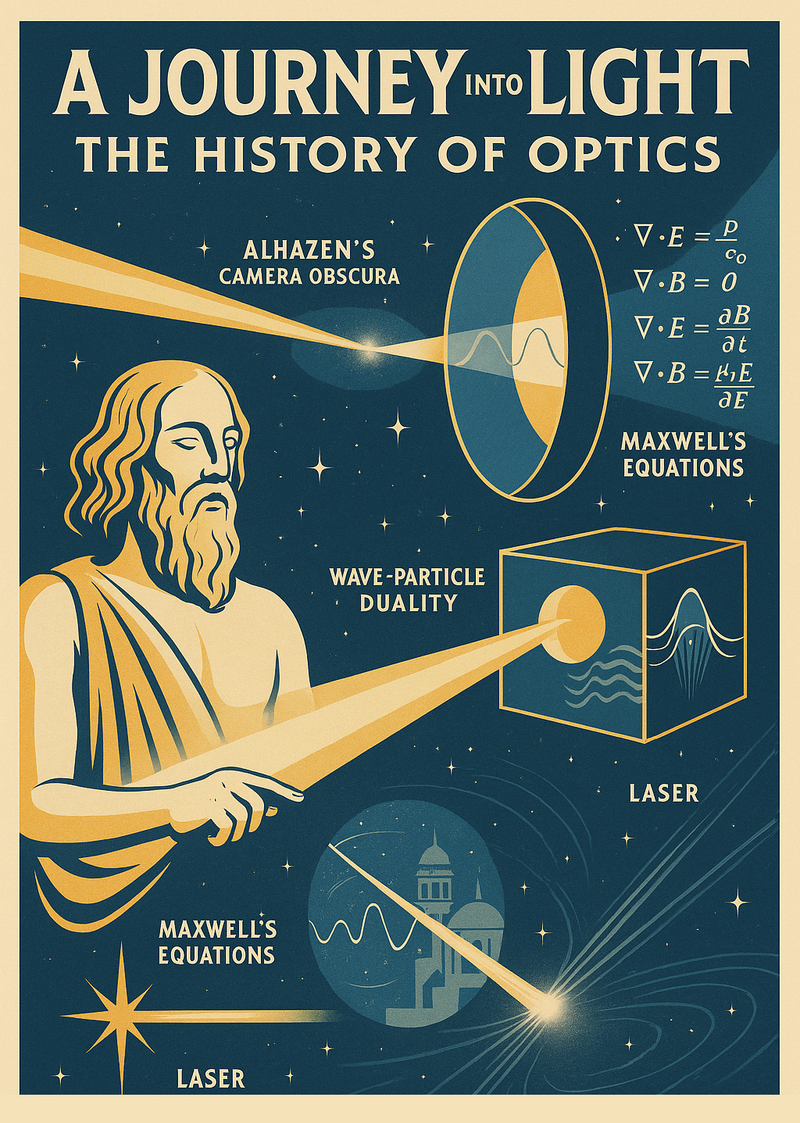

Then came Alhazen (Ibn al-Haytham) in the 11th century. Often called the “father of optics,” he wasn’t just thinking—he was testing. He used the camera obscura not just to watch, but to learn how light formed images. His methods were revolutionary: observation, hypothesis, experimentation. The scientific method itself caught a glint of light in his work.

Renaissance Refractions

“As far as we can discern, the sole purpose of human existence is to kindle a light in the darkness of mere being.”

— Carl Jung

The Renaissance exploded with lenses—telescopes, microscopes—and with them, new vision. Galileo and Kepler used glass tubes to map the heavens. But these tools were flawed: distorted images, warped colors, unreliable focus. We gained sight but questioned what we saw.

René Descartes took on the math of bending light. His work in Dioptrique tried to describe how rays moved through glass and water. Light, he said, was mechanical—a force that could be tamed, measured, predicted. Yet as precision increased, so did the mystery.

The 1800s: Waves Crash In

“In faith there is enough light for those who want to believe and enough shadows to blind those who don't.”

— Blaise Pascal

Enter Thomas Young and his elegant chaos: the double-slit experiment. He showed light acting like a wave—rippling, interfering, creating patterns no particle should make. The world blinked.

Then came Maxwell, who didn’t just study light—he unified it. His equations revealed that light is an electromagnetic wave, a vibrating dance of electric and magnetic fields.

And yet, this clarity introduced confusion: if light is a wave, why does it sometimes behave like a particle?

20th Century: The Quantum Confession

“There is a fifth dimension, beyond that which is known to man… It is the middle ground between light and shadow, between science and superstition.”

— Rod Serling

Einstein answered with the photon. Light wasn’t just a wave—it was also a particle. This duality shook physics. How could something be both continuous and discrete? Everywhere and pinpoint? Light was no longer just illumination; it became paradox.

The invention of the laser in the 1960s gave us light with discipline: coherent, focused, and powerful. It revolutionized surgery, communication, measurement. But wielding such light required navigating the complexities of quantum mechanics, material science, and chaos theory.

Present Light, Future Shadows

Today, light flows through fiber-optic cables, scans our retinas, and pushes data through the air. We bend it with meta-materials, trap it in quantum systems, and use it to image black holes. And yet, the core question remains as bright—and blinding—as ever:

What is light?

To study optics is to chase an ever-receding horizon. But in that pursuit, we see more than the world—we glimpse ourselves, trying to make sense of what was never meant to be simple.