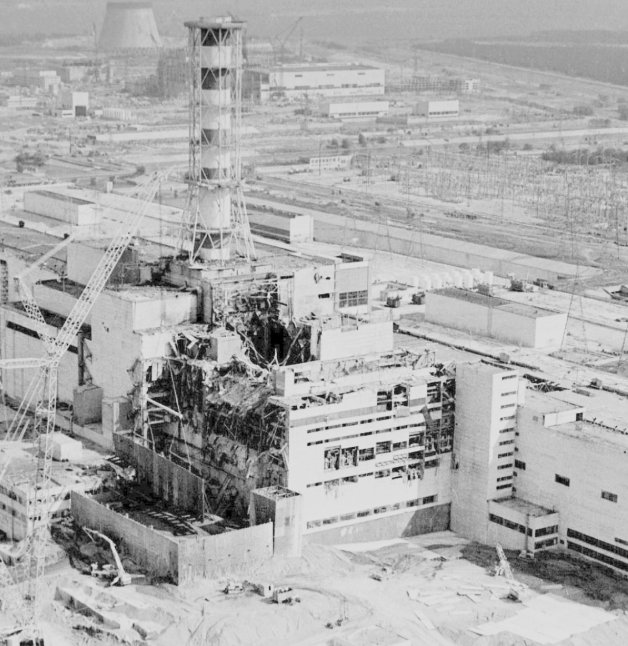

Chernobyl’s Reactor #4 — April 26, 1986 — 1:23 AM

A badly executed safety test detonated reactor #4 at the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant, launching 400 times more radioactive material into the atmosphere than Hiroshima. Firemen arrived first—brave, doomed. Their water hoses turned to radioactive steam before even hitting the reactor. They died shortly after.

In nearby Pripyat, children played in parks while radiation draped the city in silence. For three days, no one told the truth. Then came the two-hour evacuation order. 55,000 people loaded onto 1,200 buses, told they’d be gone a few days. None returned.

Pripyat became Earth’s only abandoned city of its kind—frozen in time, toxic, just three kilometers from the blast site.

Global Cover-Up, Swedish Discovery

While the Soviets kept quiet, Swedish nuclear plant workers noticed radioactive puddles clinging to their boots. A U.S. satellite later spotted the glowing core. Only then did the USSR admit something had gone terribly wrong.

Fallout of Empire

Chernobyl cost an estimated $18 billion in cleanup (equivalent to $40 billion today). It helped bankrupt the USSR. The Soviet collapse, trivia-style, had three culprits:

- Chernobyl

- The war in Afghanistan

- The cost of propping up East Germany after the Wall fell

Lava, Ice, and Naked Miners

Half a million workers were mobilized to stop the spread of radioactive lava—192,000 tons of uranium, plutonium, cesium-137, iodine-131, strontium-90, and more. The Dnepr River, and eventually the Black Sea, were at risk.

Miners dug beneath the molten mass to install an emergency cooling system. It was so hot, they stripped naked and kept digging.

On the surface, soldiers worked 45-second shifts removing burning graphite rods from reactor rooftops. Remote-controlled German tractors were brought in but suicided off the roof as their circuitry fried—“as if short-circuiting underwater.”

This was Chernobyl physics: wild, invisible, unstoppable.

The Elephant’s Foot

The most infamous artifact is the "Elephant’s Foot"—a hyper-radioactive lava formation under reactor #4. Standing near it meant death in minutes. It’s still there.

The original sarcophagus, hastily built, began to fail in the '90s. Europe stepped in to construct a second one—the New Safe Confinement (NSC)—a massive metal arch slid into place in 2016 to keep the past from leaking into the future.

Did I Go?

In 2009, I crossed Ukraine by rail. I wanted to stand alone at the gates of apocalypse. But the $700 guided tours felt clinical. I thought about bribing my way in—$50 could go far—but the bureaucracy was tighter than the zone itself.

My Kyiv driver, Nicolai, warned me: I’d need a waiver, maybe a medical. I walked around Kyiv instead. Chernobyl stayed on my shelf of dreams. Under C. And P.

A Note on Kyiv

It’s KYIV, not KEEV. Say it right. Ukrainian: “Київ.” IPA: /kɪjiu̯/. Not Russian. Not Soviet. Ky'iv.

Final Frame

Chernobyl wasn't just a meltdown. It was an unveiling. Of secrecy, of sacrifice, of science’s cold edge. It shattered lives, cracked empires, and left a ghost city as a monument to human error.