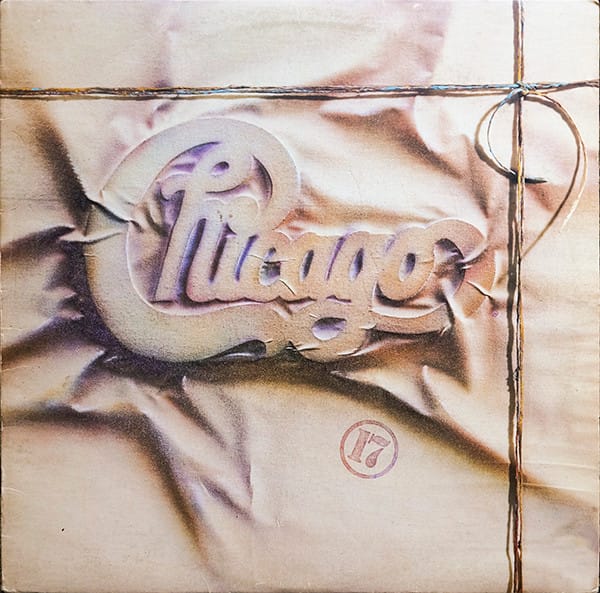

Chicago 17 and the Sovereignty of Sound

How a “syrupy” 80s album secretly perfected a craft you rarely hear

I’m not a musician. I don’t speak in chord charts or key signatures. I don’t have the vocabulary to pretend I’m analyzing arrangement the way trained people do.

But sometimes you don’t need vocabulary.

Sometimes you just need a song to hit you so cleanly it feels like driving through red lights on Memory Lane—not because you’re reckless, but because the road suddenly belongs to the past.

I can still see one specific moment like it’s lit from inside.

I was 15. It was 1984. There was a disco ball and strobe lights, and I was awkwardly dancing to “Hard Habit to Break” with someone who still owns a piece of my heart. The room was doing that teenage magic trick where everything feels like it matters forever. And for a few minutes I honestly felt like I’d arrived at adulthood—just because the lights were spinning and the song knew how to hold sadness without turning it into shame.

That’s what Chicago did.

When Chicago released Chicago 17, it was loaded with syrupy lyrics—first crushes, first heartbreaks, the kind of radio edits that slipped into your day and set up camp in your adolescence. If you grew up around it, you know what I mean: Chicago wasn’t “danger.” Chicago was permission.

They were a healthy way to enjoy sadness. A reason to look for a deeper kind of love—because they made it sound like that kind of love actually exists. And none of this echoes for me in today’s music the way it did back then.

Listening now, decades later, I finally hear why they did what they did to a generation.

It wasn’t only the lyrics.

It was the way the music carries the lyrics like a vehicle carries a passenger.

Most songs feel like words in the driver’s seat. The singer says something, and the instruments back it up. The music behaves like lighting—atmosphere, stage, support.

But Chicago 17 feels inverted.

The music leads—and the words are pulled along behind it, almost like the lyric is being towed by the melody. The syllables don’t push the song forward; they ride the current of it. The notes do the heavy lifting. The meaning comes second, but the emotion comes first, and it lands harder because it’s being delivered by something deeper than the sentence itself.

That’s what I mean by musical sovereignty.

And here’s the technical thing I can hear even without being “trained”: Chicago treats the voice like an instrument in the horn section. The melody isn’t built to carry a paragraph—it’s built to carry tone. So the lyric has to cooperate. You can hear the writing choosing phonemes and syllables that fit the notes: open vowels that can be sustained (“ah,” “oh,” “ee”), consonants that don’t choke the line, words that land their stress exactly where the groove wants it. It’s not just “what is being said,” it’s what can be sung cleanly on that pitch without losing the engine underneath.

Peter Cetera’s voice is a huge part of why this works. He doesn’t just sing the lyric—he voices it. The tone is so bright and centered it feels like a whole suite of saxophones condensed into one throat. When he holds a note, it isn’t a word anymore; it’s a sustained brass line. The band writes around that—stacked harmony, thick bass motion, guitars chugging like a train—so the vocal becomes another lead instrument riding a machine that’s already complete.

The backing track isn’t just “support.” It’s its own logic: pulse, chord movement, tension and release. The structure feels so finished you could almost place different lyrics on top and the engine would still run—because the engine is the point.

And that is rare.

Today, so much music feels engineered to highlight the vocal line, to push the hook, to flatten everything into a single lane: the lyric on top, the beat underneath, the emotion in quotation marks. It’s not that modern music has no feeling—it’s that it often feels functionally emotional, like it’s trying to do the job of sadness without actually living inside it.

Chicago lived inside it.

And there’s another layer I didn’t admit back then: they were strength.

Because when you’re a nervous teenager, there’s a social pressure to like the tough stuff—hard rock, metal, anything that sounds like armor. You weren’t supposed to say you liked Chicago. You especially weren’t supposed to say you liked the soft ones. It sat in the same category as Corey Hart: if you loved it, you loved it quietly. Guilty.

And part of that, for me, was where I grew up. My hometown had real edge—real violence in the air. “Soft” could feel like a liability. So it’s funny that Chicago—just the band name alone—sounds like it should come with brass knuckles… and yet the album I was hiding was the opposite: a record that solved problems with harmony.

Maybe that’s why it worked. The songs weren’t weak. They were controlled. They were the sound of intensity choosing restraint.

So yes—Chicago 17 is syrupy. I cannot speak to ANY other of their decades-long albums. Love loves here.

But maybe syrup is exactly what you need when you’re young: something sweet that still sticks, something that clings to memory, something that proves the heart can survive its own weather.

Chicago didn’t sell me heartbreak. They gave me a weather system—and taught me how to live inside it.

YouTube (full album): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=98bB3GWUTA8

iTunes: https://music.apple.com/ca/album/chicago-17-expanded/1107765507