TL;DR: The provided text explores the multifaceted nature of eye contact, moving beyond its role as simple nonverbal communication. It highlights how the act of meeting another's gaze signifies reciprocal awareness and establishes a shared field of perception, serving as a powerful symbol of attention and social presence. The text also discusses the cultural variability and historical significance of eye contact, noting its link to social status and power dynamics. Furthermore, it examines the neuroscientific underpinnings of mutual gaze, connecting it to affective synchrony and social bonding, while also acknowledging the cognitive load it can impose. Ultimately, the source positions eye contact as a profound phenomenological event where individual consciousness becomes intersubjectively visible and meaningful.

Eye contact is not merely a form of nonverbal communication but a deeply embedded feature of human consciousness and intersubjectivity. To meet the gaze of another is to engage in a form of reciprocal awareness—a moment when perception itself becomes mutual. The eyes serve as both signal and mirror, collapsing boundaries between self and other, and transforming the private domain of thought into a shared temporal field.

⸻

Eye Contact as Social Presence

Social psychologists have long noted that eye contact functions as a proxy for attention and engagement (Argyle & Dean, 1965). To demand that someone “look at me when I’m speaking” is to demand not only their attention but their conscious presence. The gaze acts as evidence of awareness, even though individuals can maintain eye contact while internally disengaged. Thus, eye contact is not identical to attention but serves as its most visible symbol.

The Visual Dominance Ratio (VDR) offers a quantitative model of this dynamic. Individuals of higher social status tend to maintain gaze while speaking and avert it while listening, whereas those of lower status invert this ratio. Eye contact, then, operates as an unspoken metric of power, authority, and hierarchy.

⸻

The Gaze in Historical and Cultural Contexts

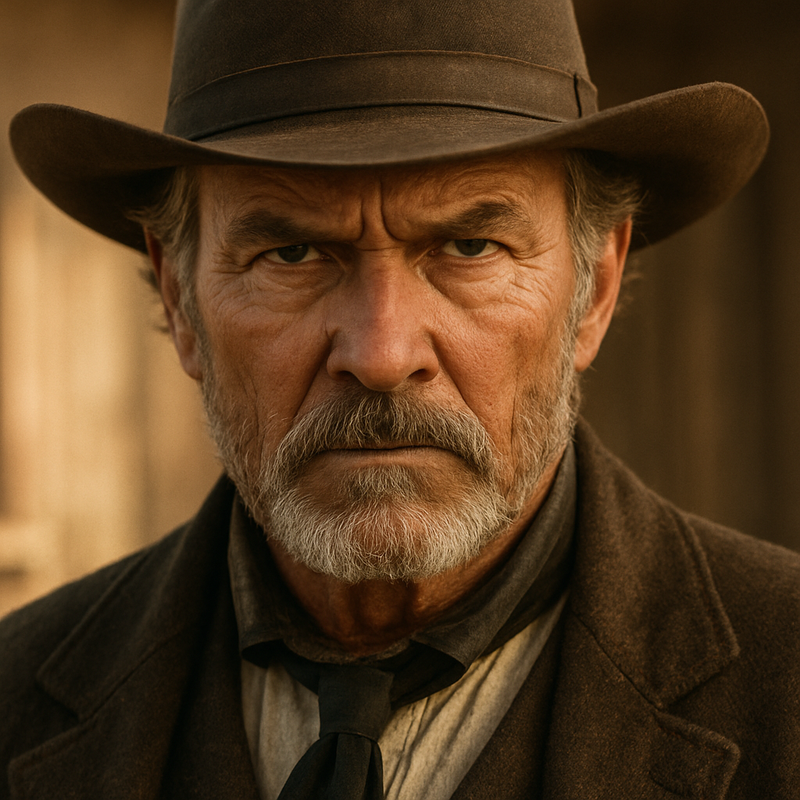

The cultural weight of eye contact is historically evident. In the American frontier—popularized as the “Wild West”—a man’s survival could hinge upon how he distributed his gaze in a saloon. A glance too long could be interpreted as a challenge; an averted gaze as weakness. Although stylized in film and folklore, this cultural logic remains in boardrooms, negotiations, and athletics, where the gaze communicates dominance, composure, and readiness.

Cross-cultural research further complicates this picture: in many East Asian societies, direct gaze is coded as disrespectful or confrontational, while in Euro-American contexts it signals honesty and confidence. The gaze is thus not universal in meaning but contextually inscribed.

⸻

The Gaze and Affective Synchrony

Neuroscientific studies reveal that direct gaze activates neural mechanisms associated with attention, emotion, and social bonding (Senju & Johnson, 2009). Sustained mutual eye contact has been shown to synchronize physiological responses, such as pupil dilation, and to increase oxytocin levels—the so-called “bonding hormone.”

This helps explain why romantic attraction is so often mediated through the eyes: the “triangle method” (shifting gaze between the eyes and mouth) and sustained mutual gaze operate as affective amplifiers, producing intimacy without words. The gaze does not merely reflect emotion; it creates it.

⸻

Cognitive Load and the Gaze

A paradox of eye contact is that it can interfere with higher-order cognition. Maintaining gaze consumes attentional resources, making it harder to solve abstract problems or recall complex information (Jiang et al., 2017). This is why individuals often avert their gaze when answering difficult questions: cognitive bandwidth must be reallocated from social monitoring to internal computation. Eye contact, then, is both a bridge and a burden.

⸻

Eye Contact as Consciousness Made Visible

Philosophically, the gaze can be understood as a phenomenological event in which consciousness becomes intersubjectively verifiable.

• To look is to enact intention.

• To be looked at is to exist in the intentional field of another.

• To share gaze is to momentarily collapse two subjective timelines into a single, co-experienced moment of awareness.

This is why the gaze can feel sacred (as in meditative or religious practice), dangerous (as in confrontation), or ecstatic (as in intimacy). Eye contact is consciousness externalized, presence rendered visible.