My vision was always just flawed enough to necessitate corrective lenses. But it wasn't the blurriness that truly frustrated me — it was a deeper, more visceral irritation: I couldn't trust my primary sensory tools. My eyes were unreliable narrators, their interpretation of reality perpetually in question. And so began an unconventional path — one that ultimately reshaped how I perceive depth and distance, especially across the infinite canvas of the night sky.

It started with a decision made under strange conditions: unilateral laser surgery at the age of 24, taken on a whim while crossing into war-torn Yugoslavia (the tickets were on sale — and hey, why not?). At the time, my prescription hovered around -1.50 to -2.0 diopters, a moderate impairment by medical standards but an existential one for someone determined to observe the world clearly. I became one of the first 100 people to undergo the procedure in my province.

The results were mixed. One eye emerged near-perfect. The other remained a blur. This asymmetry would follow me for years — across over a million kilometers, 19 countries, and countless city lights. But it was during one of those journeys, watching airplanes descend into Vancouver’s airport, that I noticed something peculiar:

The mismatched eyes didn’t hinder me.

They amplified the three-dimensionality of the flight paths.

I could see the varying altitudes — the planes weren't just dots growing larger; they became intricate vectors in motion, carving elegant arcs of descent. Their lights traced not just lines, but depth. Aerial ballet. Geometry revealed.

And then I turned my gaze upward.

The Sky, Unflattened

Years of navigating a world with visual imbalance had trained my brain differently. It had developed alternative pathways for parsing depth cues. Like a child taught to listen more closely after losing sight, my mind had compensated. But not just compensated — enhanced.

When I looked at constellations, I no longer saw flat patterns of light. Knowing the true distances between stars allowed me to mentally “stereogram” them. I felt the depth.

Take Orion’s Belt.

To most, it appears as a neat row of three stars.

To me? A trident hurled into space, its center star — Alnilam — receding far behind the other two. I could feel the stagger. My eyes adjusted as though it were a real object before me.

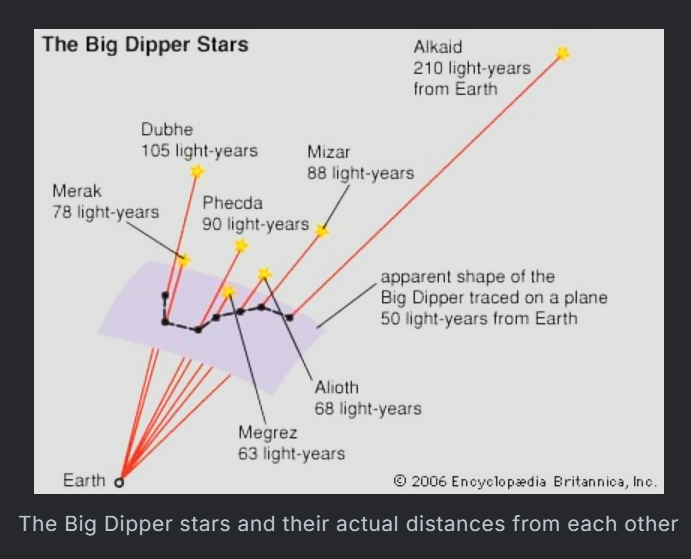

Same with the Big Dipper — a scatter of stars most see as a pattern. I see space scaffolding, the vast distances between them felt in my brow, my temples, in the subtle strain it takes to hold that impossible depth in focus.

Imperfect Eyes, Perfect Perception

What does it mean to “see”? Is it simply a matter of sharpness — 20/20 and nothing else?

Or is it something deeper — a cognitive-emotional translation of incoming photons?

My experience suggests the latter.

My “imperfect” vision opened a portal not to less perception, but to more. More dimensionality. More interpretation. A new kind of sight that collaborates with the brain rather than relying solely on retinal fidelity.

And that insight holds, whether it’s stars or smearing colors, airplane lights, or Saturn stereograms.

Yes — even Saturn.

Those Magic Eye-style stereograms that confuse most people?

I can pierce them in seconds. My brain is built for reconciling strange inputs.

A Final Note: The Cosmic Gift of Asymmetry

I rarely think about my eyes now. Maybe once or twice a week. I’ll reach for my glasses. I’ll squint at something on a rainy day.

But mostly, I’m content. Because my flawed vision gave me something no surgery could ever promise:

A mind trained to perceive the unseen depth of the cosmos.

An ability to see space not as void, but as architecture.

Not as pattern, but as structure.