In 2006, psychologists Michael F. Steger, Patricia Frazier, Shigehiro Oishi, and Matthew Kaler introduced the Meaning in Life Questionnaire (MLQ), a deceptively simple instrument that has since reshaped how we think about purpose.

Ten questions. Five probing whether you feel your life already has meaning (the Presence of Meaning scale). Five others measuring whether you are searching for it (the Search for Meaning scale).

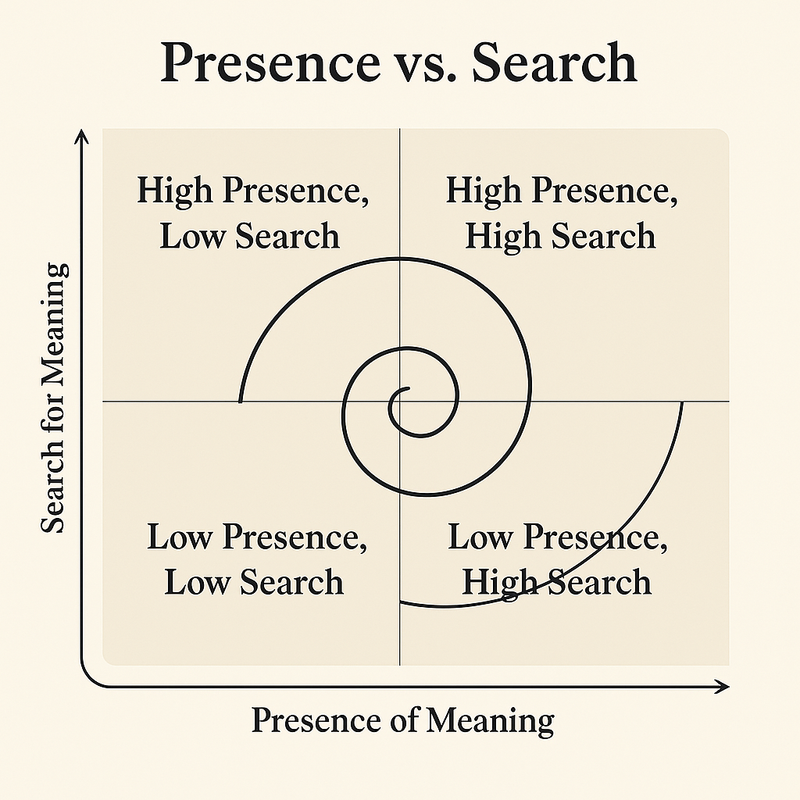

At first glance, the MLQ looks like just another psychometric scale. But its impact lies in the radical distinction it carves: you can feel that life already is meaningful, and yet still be searching. Or, conversely, you may be restless in the search while feeling very little presence of meaning at all.

This distinction dismantled decades of conflation in positive psychology and humanistic counseling. Researchers finally had a way to measure not only how much meaning people possess, but how much they pursue. The implications were profound: “search” is not simply the inverse of “presence.” It is its own psychological dimension, at times correlated, at times independent.

Beyond Psychology: The Existential Lens

For a Planksip reader, the MLQ is more than a clinical instrument. It is a mirror of existential stance.

Socrates asked whether the unexamined life is worth living. Kierkegaard declared that despair is the sickness unto death. Nietzsche pushed us to create our own values. Each, in their own way, framed meaning as both burden and possibility.

The MLQ updates this inquiry for the empirical age. It tells us:

- You can live secure in meaning (presence).

- You can live hungry for meaning (search).

- You can even live both at once, or neither.

This is not just psychology. It is measurement turned philosophy.

A Test for the Reader

Take the MLQ not as survey items, but as koans. Read each statement as if it were written for you:

- I understand my life’s meaning.

- I am searching for meaning in my life.

- My life has no clear purpose.

Then ask yourself:

- Is the “presence” of meaning a true possession, or a story you maintain?

- Does the “search” for meaning imply lack, or is it the surest sign of vitality?

- Can the restless seeker ever arrive, or is the oscillation itself the point?

From Scale to Spiral

What Steger and colleagues gave us was not just a tool but an axis. A way of mapping the recursive dance between stability and pursuit. Between “I have found” and “I must keep searching.”

Meaning, then, is not a destination, but a spiral trajectory. Presence and search are not endpoints but alternating phases, like inhalation and exhalation. To measure them separately is not to fix them, but to trace their movement.

And so the MLQ, a humble 10-item questionnaire, stands at the frontier of psychology and philosophy alike: a test not of what you know, but of how you stand in relation to knowing.

Presence of Meaning (5 items)

These measure how much people feel their lives are already meaningful.

- I understand my life’s meaning.

- My life has a clear sense of purpose.

- I have a good sense of what makes my life meaningful.

- I have discovered a satisfying life purpose.

- My life has no clear purpose. (reverse scored)

Search for Meaning (5 items)

These measure how much people are actively seeking or striving for meaning.

6. I am looking for something that makes my life feel meaningful.

7. I am always searching for something that makes my life feel significant.

8. I am seeking a purpose or mission for my life.

9. I am searching for meaning in my life.

10. I am looking for something that makes my life feel significant.

Reference:

Steger, M. F., Frazier, P., Oishi, S., & Kaler, M. (2006). The Meaning in Life Questionnaire: Assessing the presence of and search for meaning in life. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 53(1), 80–93.