In a world of endless languages, one mutant tongue has slipped through the chaos and risen to global dominance—not by purity or perfection, but by flexibility and brute cultural force. That language is English. And its final form? Broken.

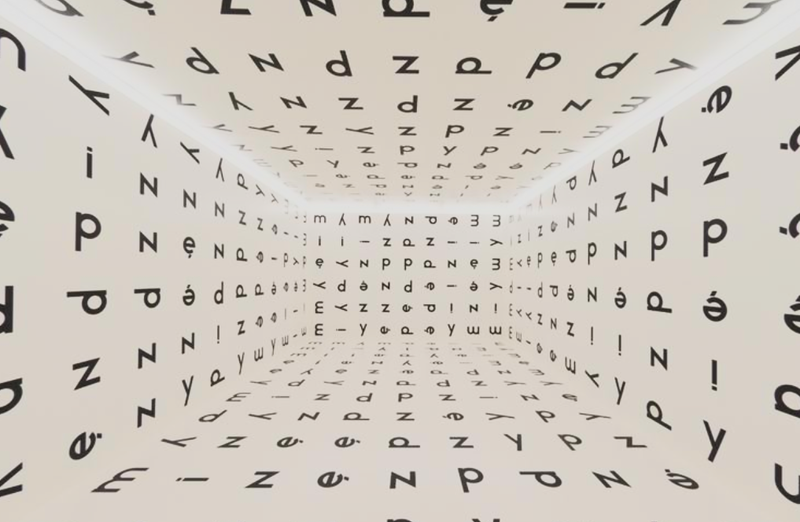

We speak, think, and code our lives using just 26 letters and 10 digits. With those symbols, we describe everything from heartbreak to rocket science, from TV dinners to time travel. Language isn’t just a tool—it’s cognition externalized. The better your vocabulary, the sharper your tools for navigating the world. And no toolkit has spread like English.

Unlike the Latin-rooted tongues it evolved alongside, English is a Frankenstein’s monster—stitched together from Germanic roots, French aristocracy, Norse invasions, and Roman law. It’s not elegant. It’s not consistent. But it works—and that’s why it won. Where other languages cling to gendered nouns, rigid grammar, and unbending structures, English flexes.

You can abuse English and still be understood. You can mangle syntax, murder pronunciation, and toss grammar out the window—yet English will bend, not break. A Ukrainian engineer, a Colombian barista, a Nigerian coder, and a South Korean gamer can all sit down, speak in jagged fragments, and still make a deal, share a joke, or build a startup.

As someone who taught English from beginner to advanced levels at schools and universities in Russia, China, and Iraq, I’ve seen this firsthand. Some people race ahead—learning fast, speaking fluently, mastering nuance. But others? They hit a functional plateau and stay there. And they’re fine with that. They’ve reached a “working English”—the level needed to navigate jobs, shopping, social media. It’s not fluent, it’s not poetic, but it’s enough. And in a world of linguistic chaos, enough is power.

English is the global second language. Not because it’s beautiful. Because it’s inevitable.

Esperanto Lost. English Didn’t Even Compete.

In 1887, L.L. Zamenhof launched Esperanto—designed to be the world’s universal language. Simple, neutral, logical. It had everything but traction. Today, maybe a few thousand speak it fluently. Meanwhile, over 1.5 billion people speak English. Nearly 400 million are actively trying to learn it right now. Esperanto was the future. English is the present.

Colonization Lit the Fuse. Globalization Exploded It.

British colonialism made English the official language of 75 nations. That was the foundation. But it was American hegemony that turned it into a linguistic tsunami. Post-WWII, the U.S. exported its media, its military, its markets—and its mouth. From CNN to Coca-Cola, Hollywood to Apple, if you wanted to engage with the future, you had to do it in English.

And so people tried.

Desperately. In schools, in cafés, on phones. With pirated DVDs, pop lyrics, and textbooks. Even if they didn’t understand a word, they watched. They listened. They mimicked. Because comprehension meant upward mobility. It meant status. It meant survival.

Broken is Beautiful

Nobody starts with Shakespeare. Most people start with “My name is.” Then they build. Bad grammar? Who cares. Thick accent? No problem. This is Broken English—an ever-shifting, beautifully bastardized version of the original, built for global collaboration.

In this world, mispronunciation is a feature, not a bug. Grammar is a guideline, not a rule. Fluency is measured not in poetry, but in mutual understanding.

You can be wrong and still be right. You can butcher tenses, drop articles, and still land the deal, make the friend, get the job. That’s what makes English uniquely suited for global use—it has already adapted to its broken forms.

French is Too Proud. Chinese is Too Pictographic.

French has too many gender rules, too many accents, too much linguistic pride. The Académie Française tries to protect it like an endangered species. Chinese, while spoken by over a billion, demands mastery of thousands of pictographs and tonal shifts that most foreigners will never crack. Besides, digital encoding favors alphabets.

English isn’t better—it’s just more willing to be broken.

Half the Internet Still Speaks English

Even as other languages gain ground online, English still dominates the web, academia, aviation, science, business, and pop culture. It’s the default in international meetings, Zoom calls, air traffic control, and startup pitches. It’s the baseline. And it’s increasingly non-native.

The future isn’t fluent English—it’s functional English.

The Test is the Status Symbol

In places like India, China, Nigeria, and Brazil, your English test score is your class marker. It’s your passport. Your proof of cultural capital. A high TOEFL or IELTS score can open doors to universities, visas, and jobs. A low score can shut them permanently. It’s brutal. It’s invisible. It’s happening everywhere.

And Still, They Try

Because behind the broken phrases and misused idioms is a dream: to be understood. To be included. To be part of the global conversation.

Even the Baha’i faith predicted it. Two languages: one for your country, one for the world. That second one? It’s not Latin. It’s not Swahili. It’s not Mandarin.

It’s English. And not even “correct” English.

It’s the broken kind—the kind spoken in train stations, on TikTok, across war zones and call centers and cafés. It’s the kind that bridges billionaires and refugees, astronauts and schoolchildren.

That’s the truth.

The universal language of the future isn’t English.

It’s broken English.

And that’s a damn beautiful thing.