Ernest Hemingway wasn’t just a writer — he was a storm system in human form. Born in 1899, dead by his own hand in 1961, he lived like his prose: stripped of excess, wired with danger, and aimed dead at truth. He didn’t just write stories; he inhabited them. War correspondent, fisherman, bullfighter, drinker, hunter, lover — Hemingway built a life so large it sometimes dwarfed the books that made him famous.

“The world breaks everyone, and afterward, some are strong at the broken places.”

That single sentence explains both the man and his work. Hemingway’s life was a collision of trauma and toughness — the boy from Oak Park who went to war as an ambulance driver, got blown apart, then spent decades chasing the next wound that might make sense of the first one. He covered wars, hunted lions, survived two plane crashes, and out-drank entire continents. Every injury became source material; every scar, a sentence.

The Man Who Made Simplicity Dangerous

Hemingway’s great trick wasn’t minimalism for its own sake — it was compression under pressure. His “iceberg theory” said the deeper meaning of a story lives beneath the surface. What’s written is only the tip; what’s felt is the mass below.

He wrote in:

- Short, declarative sentences.

- Concrete nouns and active verbs.

- Objective observation, not confession.

- Dialogue that carries the emotional freight.

Consider this from A Farewell to Arms:

In the late summer of that year we lived in a house in a village that looked across the river and the plain to the mountains.

Nothing ornamental, no psychological exposition — yet the quiet foreboding hums in every stone and shadow.

Or this from The Sun Also Rises:

“Oh, Jake,” Brett said, “we could have had such a damned good time together.”

“Yes,” I said. “Isn’t it pretty to think so?”

Seven words of resignation that have outlived entire treatises on heartbreak.

“There is nothing to writing. All you do is sit down at a typewriter and bleed.”

He meant it. His stories are the literary equivalent of shrapnel — small, sharp, and lodged permanently in the reader.

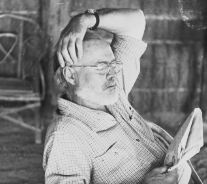

The Persona: “Papa” Hemingway

By midlife, Hemingway had become both man and brand. The beard, the khakis, the drink — the living embodiment of the myth he helped invent: rugged masculinity staring death in the face and writing it down before breakfast.

He spent years in Cuba, wrote For Whom the Bell Tolls, chased marlin, loved fiercely, and quarreled endlessly. Beneath the bravado was a craftsman obsessed with clarity. Every line he cut was a small act of worship to truth.

“The best way to find out if you can trust somebody is to trust them.”

He trusted the sentence — not adjectives, not explanation — just the pulse of what is.

The Legacy

Hemingway won the Pulitzer in 1953 for The Old Man and the Sea, and the Nobel the following year. But awards were only the formalities; his real victory was changing the way English breathes. He taught us that a single clean line could say more than a page of flourish.

His influence runs through every modern writer who trims a sentence and every journalist who believes clarity is courage. Yes, his myth has been parodied, his machismo debated, but his best work still stands — lean, defiant, alive.

“Never go on trips with anyone you do not love.”

Maybe he was giving travel advice. Maybe he was talking about life.

So Who the Hell Was Hemingway?

He was the man who made understatement thunder.

A hunter who wrote tenderness with a bayonet’s edge.

A man of action who believed the truest art was restraint.

He lived hard, wrote harder, and left behind sentences that still feel carved out of bone and saltwater.

Hemingway didn’t just change literature. He changed how we talk about truth — what we can say, and what we have to leave unsaid.

“We live by the stories we tell — and Hemingway’s are still out there, smoking on the bar top, waiting to be read again.”

🎧 [Sound design cue: a single typewriter keystroke echoing into silence.]